Notebook

Vocabulary: Record the following vocabulary in your notebook. As you complete the learning activity fill in the definition and key terminology pertaining to the vocabulary.

- constructive Interference

- destructive Interference

- superposition

- nodes

- antinodes

- loops

Introduction

Now that we know some of the characteristics of waves, let’s consider what happens when two one-time waves (also referred to as pulses) meet each other when they travel in the same medium.

Have you ever watched waves ripple out after dropping something in the water? What happens if you drop two objects close to each other? Do the waves from each object interact with each other? This is the question we will be investigating further in this learning activity.

Wave interference

As you may have guessed, for the short period of time that the pulses spend passing through one another, they do interact, and this interaction is called interference.

Explore this!

The following video is a demonstration of two waves interfering.

Wave interference occurs when two or more waves interact at the same time in the same medium.

Definition

Amplitude is an important concept used in interference. Amplitude is the distance from the equilibrium line. When the wave is above the equilibrium line, it has a positive amplitude. When it is below the equilibrium line, it has a negative amplitude.

Now, let’s study the two types of interference: constructive interference and destructive interference.

Constructive interference

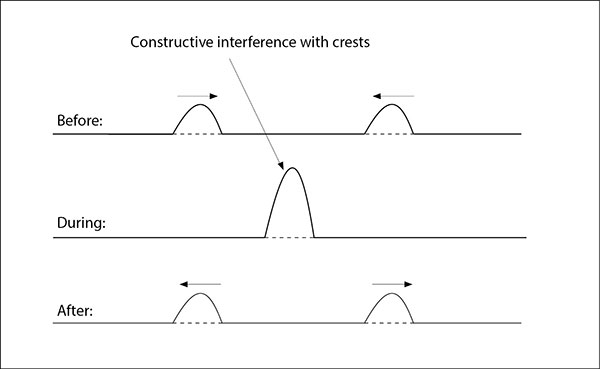

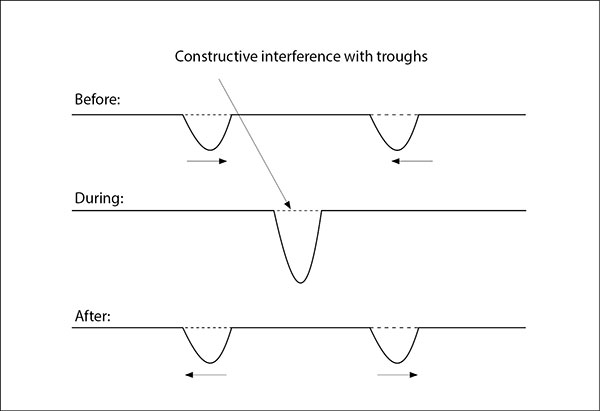

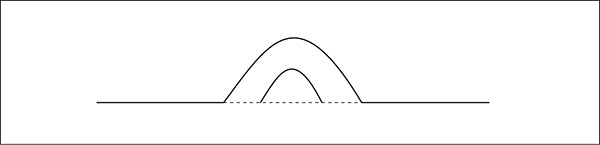

Constructive interference occurs when a crest interferes with a crest, or a trough interferes with a trough. In these cases, the two pulses will add together to form extra-large crests (called supercrests) or extra-large troughs (called supertroughs). The following two diagrams illustrate examples of constructive interference: the first with crests, and the second with troughs.

Both diagrams illustrate the two pulses before they meet, and then again during the time they interfere. At this point, the two pulses are superimposed on each other, just for an instant. Note that the amplitude of the supercrest/supertrough is the sum of the two amplitudes of the two smaller pulses. You can determine the superimposed amplitude by just adding the two amplitudes of the original pulses. Also notice that the two crests illustrated in the previous diagram just pass through each other and are unchanged afterwards and this is also the same case for the two troughs, as shown in the following diagram.

Destructive interference

For destructive interference, things are very different.

Explore this!

The following video is a demonstration for destructive interference.

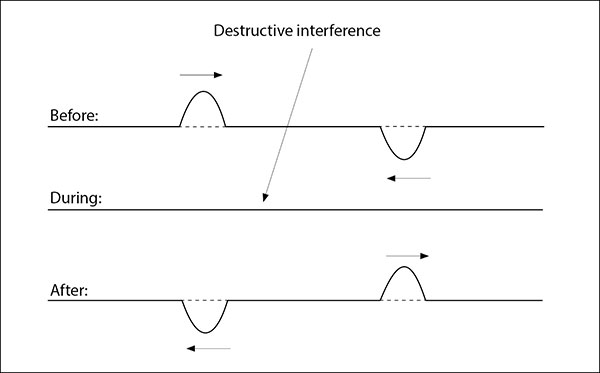

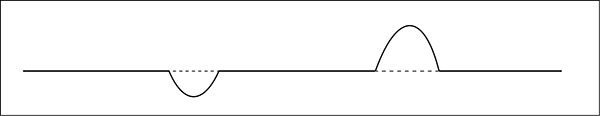

In this case, a crest is superimposed on a trough. When the two meet during interference, the crest attempts to pull the particles in the medium up, while the trough attempts to pull them down. The two actions cancel each other out and the resultant wave has a lower amplitude than either pulse. The following diagram illustrates a crest and a trough with equal amplitudes interfering.

Note that, in this case, you can observe two things that were not completely obvious in the constructive interference examples. This case clearly illustrates that the pulses do pass through each other and don’t bounce off. During the interference, the amplitude is zero because the positive and negative amplitudes add up to zero, as shown in the following illustration.

Principle of superposition

At any point in a medium, the resulting amplitude of two interfering waves is the algebraic sum of the individual displacements of each wave.

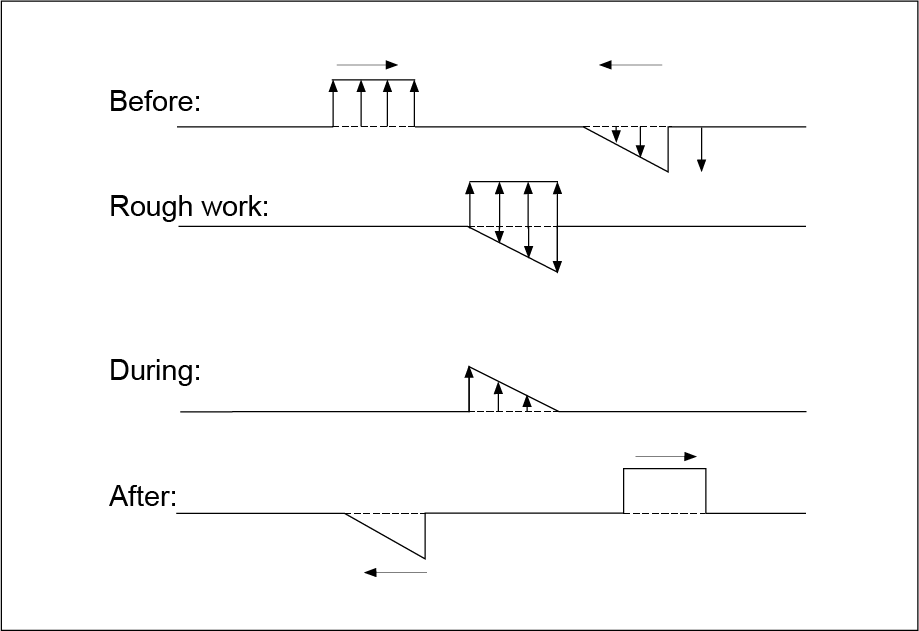

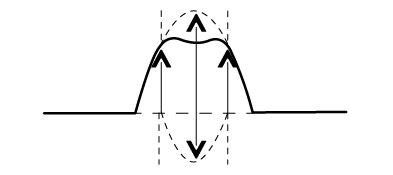

Examine the following diagram to help you understand the process better. To find the displacement of any particle in the medium, add the algebraic amplitudes for each individual wave. Keep in mind that displacements above the equilibrium (from crests) are positive and displacements below the equilibrium (from troughs) are negative.

If you examine the rough work step, you can observe that on the left side of the superimposed waves, the displacement of the rectangular crest is positive, but the triangular trough has no displacement. This means that the resultant displacement will be positive and equal to the displacement of the rectangular crest. On the right end of the superimposed waves, the two displacements are equal in magnitude, but opposite in direction.

At this point, they cancel each other and there is no displacement. In between the two ends, the positive displacement of the rectangular crest is always greater in magnitude than the negative displacement of the triangular trough. This results in a smaller positive displacement for each point in between the two ends. Afterwards, the pulses just pass through each other, unchanged.

Example: Principle of superposition

Using the superposition principle, determine the resultant displacement of the particles in the medium at the instant shown in following diagram.

Notebook

You can use your notebook to complete the following question. Compare your work with the solution to check your understanding.

- Using the superposition principle, determine the resultant displacement of the particles in the medium when the horizontal midpoints of the two pulses overlap, as shown in the following diagram.

The resulting midpoint of the two pulses overlapping using the superposition principle would appear to be as shown in the following diagram.

Beats

When two nearly identical frequencies are sounded together, a strange thing happens. To examine what happens, you can take two identical tuning forks and place an elastic band around the tines of one of them. The elastic band will lower the frequency of the tuning fork slightly. When one tuning fork is sounded on its own, a person can hear a single frequency of constant sound. When the two are sounded together, a person can hear dramatic changes in the loudness of the sound at regular time intervals. Typically, the sound will be heard as a loud-soft-loud pattern. This pulsating pattern represents the constructive and destructive interference of the two tuning forks with the slightly different frequencies.

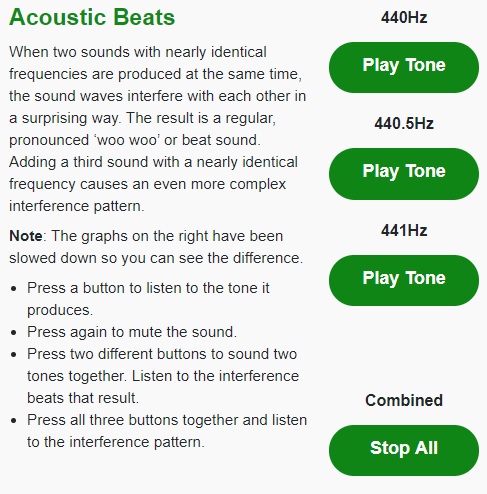

Try it!

Let’s simulate these phenomenons of constructive and destructive interference in the following interactive simulation.

In the simulation, a person could hear something like, “woo—woo—woo—woo.” The “woos” you hear are called beats. The three different frequency in the simulation are 440 Hz, 440.5 Hz and 441 Hz.

Press Enter here for an accessible version of “Acoustic beats.”

Why do you hear beats?

These beats occur because the sound waves from the two sources are shifting in and out of phase (the waves are no longer in sync with each other). When they are in phase, the sounds get louder because they are interfering constructively and a person could hear the “woo” sound. When they are out of phase, the sound is very faint because they are interfering destructively.

What is beat frequency?

The number of beats heard per second (beat frequency) is equal to the difference in the frequency of the two sounds.

Why are there beats?

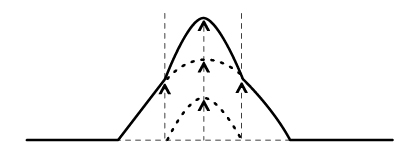

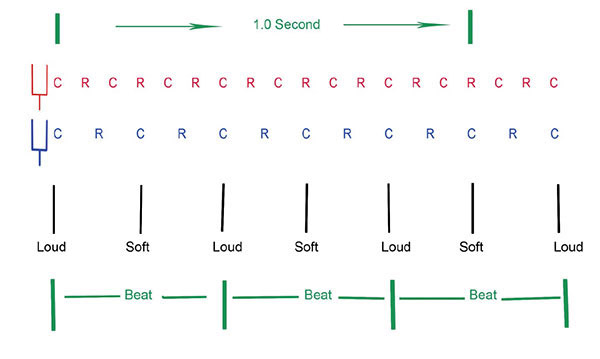

The “woos” are called beats and the number of beats produced in a given amount of time is called the beat frequency. These beats occur because the sound waves from the two tuning forks are shifting in and out of phase. When they are in phase, the sounds get louder because they are interfering to form two beats over a short amount of time, as shown in the following diagram. To keep things simple, assume that the time is a little over one second.

Note: The frequencies used would not be high enough for a person to hear, but the diagram is provided just to help describe the concept of beat frequencies.

Note: The diagram that the top sound source sends out eight compressions (C) and rarefactions (R) in one second. Its frequency is 8.0 Hz. The bottom sound source has a frequency of 5.5 Hz. The difference in frequencies is 2.5 Hz.

As the two sound waves move out, sometimes they interfere constructively to create a loud sound, sometimes destructively to create a soft sound, as shown in the diagram. In the one second interval used, the two waves create 2.5 beats.

Beat frequency equation

The following beat frequency equation is:

Formula

fb = |f2 - f1|

Where:

fb is the beat frequency

f1 and f2 are the frequencies of the two tuning forks (or any other sources of sound).

The two vertical lines mean absolute value. They indicate that the beat frequency must be positive. If the difference between the two frequencies as illustrated were negative, you would just drop the minus sign and make it positive. To avoid this problem, you can always just subtract the lower frequency from the higher one.

Example: Frequency of tuning forks

Two tuning forks with slightly different frequencies are sounded together. One has a frequency of 256 Hz and the other has a frequency of 253 Hz. They are sounded together.

a) What is the beat frequency?

b) The 256 Hz fork is removed and replaced with a new fork. Now when the two tuning forks are sounded together, you hear 10 beats in 5.0 s. What is the new frequency of the weighted fork?

Portfolio

Try the following questions on your own in your notebook.

1. Tuning fork 1 (420 Hz) is sounded along with tuning fork 2 and 20 beats are counted in 10 s. Tuning fork 2 is sounded along with tuning fork 3 (426 Hz) and 12 beats are detected in 3 s. What is the frequency of tuning fork 2? Explain your reasoning.

2. Tuning fork 1 (256 Hz) is sounded along with tuning fork 2 (255 Hz). What is the beat frequency?

3. Elastic bands are attached to tuning fork 1 (which was 256 Hz) to reduce its frequency. It is sounded again with tuning fork 2 (255 Hz), making 12 beats in 6.0 s. What is the new frequency of tuning fork 1? Explain your reasoning.

Try it!

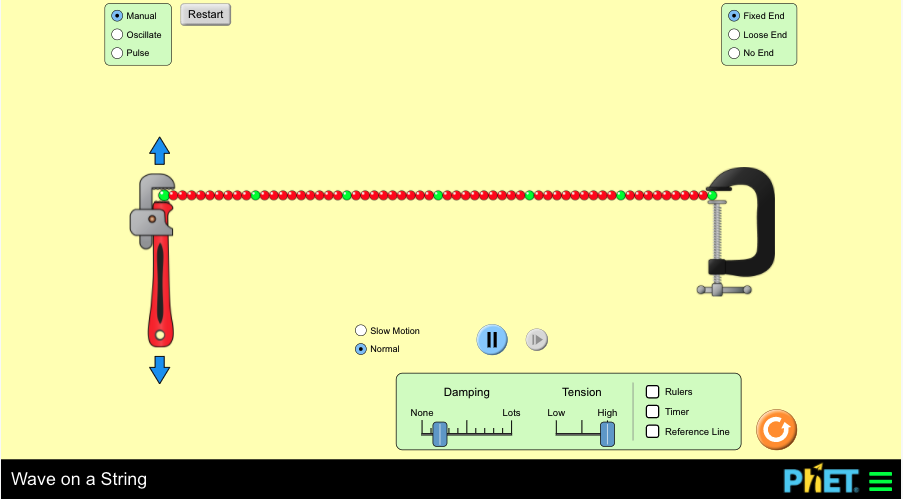

Read the following instructions before trying the wave on a string stimulation:

- In the top left corner choose oscillate, and in the top right corner, choose fixed end.

- Along the bottom, set frequency to 2.00 Hz.

- Set damping to none.

- Set tension to halfway between high and low.

It is easier to observe what is happening if you select slow motion. Start the following simulation and observe. Is the wave swinging up and down rather than travelling through the string?

Press Enter here for an accessible version of “Wave on a string.”

Standing Waves

Waves – especially sound and light waves – often travel very quickly, making them difficult to study. In this section, you will learn about a way to study waves so that the properties of a wave are much easier to observe. This method involves using two identical sources that send out waves in opposite directions. It is crucial that both waves have an identical wavelength and amplitude in order for this interference pattern to work. The wave pattern that is produced using this method is called a standing wave because it appears to have no wave motion, only particle motion.

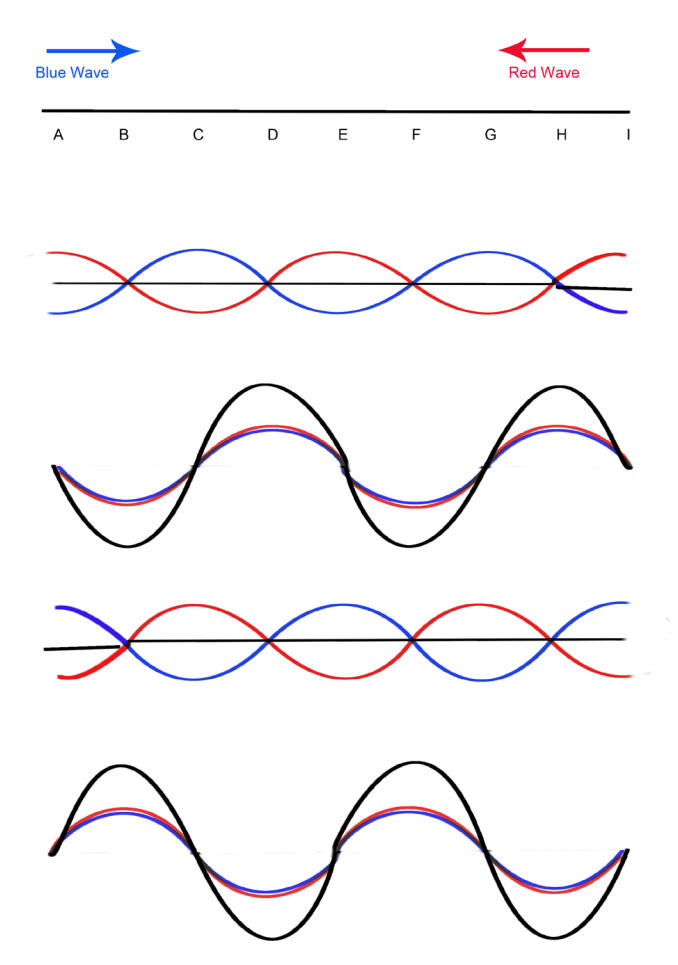

In the diagram beside, two waves (shown in red and blue) move in opposite directions through the same medium. The subsequent diagrams show what happens as the red and blue waves move from point A to I (and vice versa).

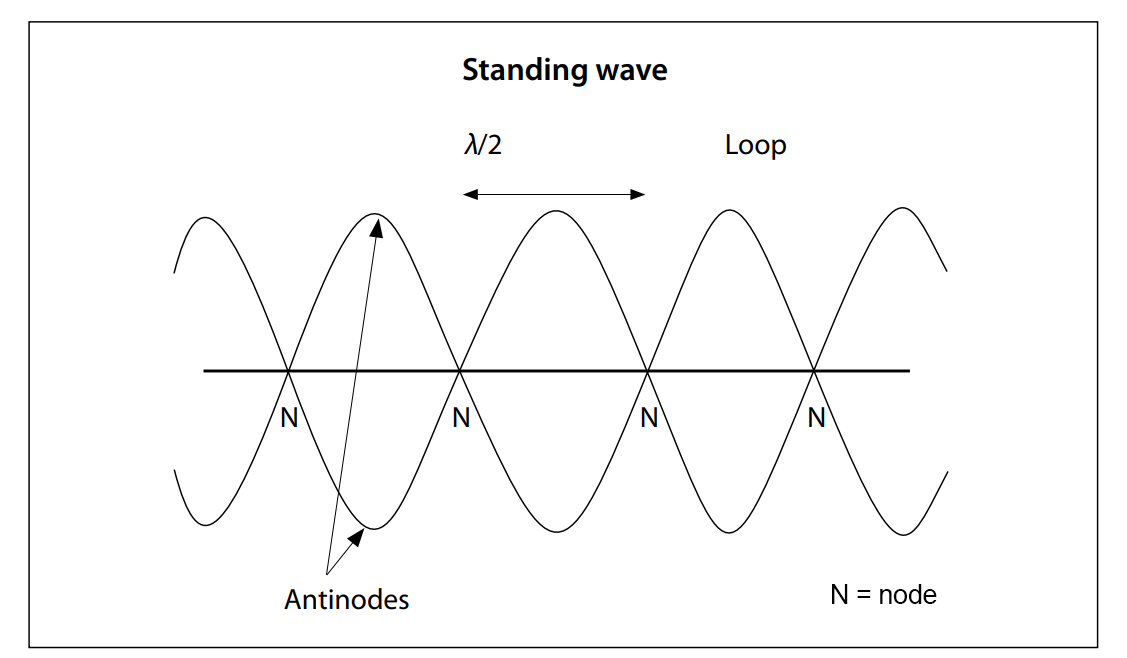

When two identical waves moving in opposite directions in a medium interfere, there are points in the medium that do not move at all. These points are called nodes (N). The points occur at positions in the medium where crests meet troughs.

As you learned earlier, the destructive interference for identical waves produces no displacement at all and the particle remains at rest. Midway between the nodal points, there are points called antinodes. These points occur at positions where troughs meet troughs, forming supertroughs, and where crests meet crests, forming supercrests. The resulting constructive interference produces displacements twice as large as the displacements of the source.

If you observed a standing wave, you would notice that the nodes stay at rest, never moving, while all of the other points move back and forth, perpendicular to the wave motion. The antinodes would be located where the particles have the largest displacement.

Standing wave simulation

When two identical waves moving in opposite directions in a medium interfere, there are points in the medium that do not move at all. These points are called nodes (N), as shown in the following diagram. Midway between the nodal points, there are points called antinodes, in the illustration. The following diagram of the standing wave has four nodes, six antinodes, and three loops.

One of the more useful properties of standing waves is the fact that the distance from one node to the next (one loop) is half a wavelength. Since these points don’t move, it’s very easy to measure the wavelength.

The width of one loop is half a wavelength, so the width of two loops will be one wavelength:

1 loop = λ/2

2 loops = λ

Example 1

The distance between two successive (one right after the other) nodes in a standing wave is 20 cm. The frequency of the source is 15 Hz. Find the speed of the waves.

Example 2

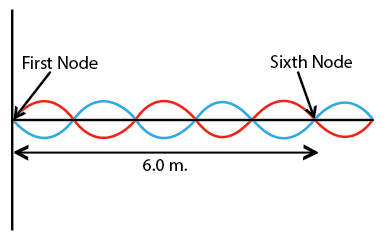

A vibrating source makes a standing wave in a string as shown in the following diagram. The source moves up and down, completing 22 cycles in 5.5 s. The distance from the first node to the sixth node is 6.0 m. Find the speed of the waves.

Portfolio

Try these on your own in your notebook.

1. A source with a frequency of 30 Hz is used to make waves in a rope 12 m long. It takes 0.20s for the waves to travel from one fixed end of the rope to the other. What is the speed of the wave? What is the wavelength? How many loops are there in the standing wave in the rope?

2. Two waves travelling in opposite directions at 6.0 m/s produce nodes that are 0.40 m apart. What is the wavelength? Find the frequency of the waves.

3. You tie the two opposite ends of a long rope to fixed positions. You have a source that can set up standing waves in the rope, a metre stick, and a stopwatch. Describe a procedure you could use to find the speed of the waves in the rope using the principles of standing waves.

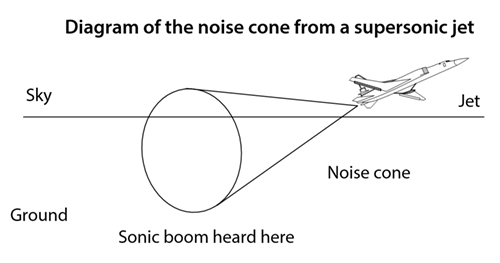

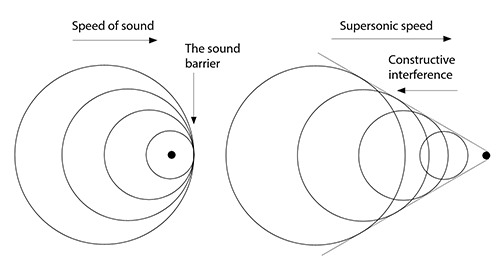

Sonic booms

If an object is travelling at a speed that is less than the speed of sound, it is said to have subsonic speed. If it travels at a speed that is greater than the speed of sound, it has supersonic speed. To accomplish this feat, the object must first break through the sound barrier. Typically, jets are used to break the sound barrier, although some experimental cars have also accomplished this task.

Explore this!

Try answering the preceding questions based on the following animation:

1. Do waves bounce off each other when they meet or do they pass through each other?

The waves pass through each other. The second animation demonstrates this best as the top wave continues to the right after the waves interfere with each other.

2. What happens to the shape of the wave when they are in the same space?

The shape of the wave changes but once they pass through each other the waves return to their original shape.

Review

Refer back to vocabulary list at the beginning of this learning activity. Verify your understanding of each word. Have a definition and related use of the word in a sentence for your learning activity.